BBC Eye Investigations report, 12 April 2023. A multinational scam network has defrauded ordinary investors out of over a billion dollars. A clandestine network of merchants appears to be behind it, according to BBC Eye.

Then you hear the phone ring. An old man responds. The caller describes himself as “William Grant” from Solo Capitals, a trading firm. He claims to have a “great promotion” for you. The elderly man appears weak and befuddled. “I’m not interested; I’m not interested,” he said. But William Grant is tenacious. “I only have one question,” he says to the elderly gentleman. “Are you interested in making money?”

Trading Scams

Jan Erik, a 75-year-old pensioner in Sweden, is about to be duped once more. The call came from the offices of Solo Capitals, an ostensibly cryptocurrency trading organization situated in Georgia. The recording is difficult to listen to since the old man, Jan Erik, not only sounds incoherent, but he also tells the caller that he has already lost one million Swedish Krona (approximately £80,000) in trading frauds.

But the caller is well aware of this. And he knows it makes the pensioner a prime target for a subsequent “recovery scam.” He informs Jan Erik that if he provides his credit card information and makes a €250 deposit, Solo Capitals will use special software to track down and recover his lost investments.

“We’ll be able to recover the entire amount,” William Grant predicts.

It takes him a bit to wear down Jan Erik. However, after roughly 30 minutes on the phone, the elderly man starts reading out his credit card information.

The company labeled the audio recording “William Sweden scammed.” The BBC received the material from a former employee, but the company did not make any attempt to conceal it. In fact, it had been distributed to new hires as part of the company’s training program. This was a tutorial on how to con people.

BBC Eye has been investigating a global fraudulent trading network of hundreds of distinct investment brands that have defrauded unwitting consumers like Jan Erik out of more than a billion dollars for more than a year.

For the first time, our investigation shows the magnitude of the fraud as well as the identity of a shadowy network of people who appear to be behind it.

The network is known to authorities as the Milton Group, a moniker coined by the scammers but dropped in 2020. We discovered 152 brands that appear to be part of the network, including Solo Capitals. It preys on investors and defrauds them of tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of pounds.

One Milton group investment brand even sponsored a top-tier Spanish football club and advertised in major newspapers, establishing trust with potential investors.

In November, BBC Eye joined German and Georgian police on call-center operations in Tbilisi, Georgia. We observed row after row of British phone numbers on the computer screens. We called a few and spoke with British citizens who said they had just invested money. On one desk, there was a handwritten note with a list of names and essential information for scammers: “Homeowner, no responsibilities”; “50k in savings”; “From Poland, British citizen”; “50k in stocks.”

A note next to the name of one British man wrote, “Savings less than 10,000, very pussy, should scam soon.”

The majority of victims sign up after viewing a social media advertisement. Typically, they receive a phone call within 48 hours from someone telling them they may make up to 90% returns per day. On the other end of the phone, there is usually a call center that has many of the trappings of a real business, such as a smart, modern office with an HR department, monthly targets and bonuses, awaydays, and competitions for best salesman. Some contact centers have thumping music playing in the background. However, there are components that you will not find in a real firm, such as written guidance on how to discover and exploit a potential investor’s flaws.

Victims may be steered into licensed corporations or, in some cases, unregulated, offshore entities from the initial phone conversation. Some victims who signed up to regulated brands within the Milton group were directed by their broker to conduct high-risk trades that were likely to lose money for the customer while making money for the broker. Some victims are directed to download software that allows the scammer to remotely manage their computer and place transactions on their behalf. According to former Milton group branded employees, some clients believe they are making legitimate trades, but their money is just being siphoned away.

“The victims think they have a real account with the company, but there isn’t really any trading, it’s just a simulation,” Alex, a former employee at a Milton group office in Kyiv, Ukraine, explained.

The BBC posed as an aspiring trader and contacted Coinevo, one of the Milton group’s trading platforms, to better understand how the fraud works. We were connected to an adviser named Patrick who claimed we could make “70%, 80%, or 90% in one single day.” He instructed us to transfer $500 in Bitcoin as a deposit in order to begin trading.

Patrick pressured our undercover trader to submit a copy of their passport, and after supplying a forged copy, we were able to keep the account open for nearly two months until Coinevo discovered the forgery. Patrick sent us an email at that point, cursing us and severing contact.

However, the BBC’s deposit was already in the system. We were able to monitor it as it was divided into small pieces and moved via numerous Bitcoin wallets, all of which appeared to be affiliated with the Milton group. According to experts, reputable financial organizations do not channel money in this manner. Louise Abbott, a cryptocurrency and fraud lawyer, reviewed the money movement and concluded that it indicated “large-scale organized crime.” Abbott explained that the money was split over multiple bitcoin accounts to “make it as complicated and difficult as possible for either you, the victim, or us as lawyers to find.”

The ideal target

Victims of these telephone trading scams are frequently exploited because of their financial and social conditions. People who expose significant sums of money are compelled to make large investments. Scammers approach lonely people and make them their friends. Jane (whose name has been changed for this narrative) was an ideal target as a recent retiree. She had recently accepted voluntary redundancy and had a lump amount of over £20,000 that she thought, if prudently invested, could supplement her pension in the coming years. During the first lockdown in June 2020, she noticed an ad online for a firm named EverFX.

EverFX was one of the primary sponsors of the top-flight Spanish football team Sevilla FC at the time, and the club’s stars had publicized the trading platform on social media, and it was licensed by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority, Jane said.

Jane contacted EverFX via their website and was contacted and connected to someone she was assured was a senior trader. He introduced himself as David Hunt and said he was calling from Odessa, Ukraine. Jane thought his accent sounded Eastern European, but she couldn’t place it. She liked him right away.

“He really knew his stuff, he knew how all the markets worked,” she told me. “I really got into it.”

Soon, they were talking practically every morning, and Jane was exposing specific things she needed money for – pricey roof repairs, a pension cushion. Hunt allegedly used them against her, telling her that certain transactions would “get her that roof” and “help her future.”

Jane invested around £15,000 over the next few months. But her business was struggling. Hunt recommended her to withdraw her funds and invest with another trading site, BproFX, where she may earn higher profits.

Jane had completely trusted David Hunt by that moment. “I felt like I knew him well, and I thought he had my best interests at heart,” she sobbed. “So I agreed to move with him.”

She had no idea BproFX was an uncontrolled offshore corporation situated in Dominica. In actuality, EverFX’s UK regulatory status does not prevent it from defrauding British citizens, but switching to BproFX would deprive Jane of even the meager protections granted to her under UK law. The BBC discovered multiple victims who were transferred to unregulated companies in this manner.

Jane agreed to invest £20,000 in BProFX in September 2020, and Hunt trained her through numerous trades over the next six months. However, she continued to lose money.

Other victims informed the BBC that they had been duped in this manner. Londoner Barry Burnett said he began investing after seeing an EverFX advertisement, but after a few early gains, he lost more than £10,000 in 24 hours. The consultant persuaded him to put in another £25,000 in order to trade himself out of his hole.

“I must have got at least half a dozen calls in the space of about two hours,” Barry told me. “People begging me to put more money in.”

David Hunt put similar pressures on Jane. “He kept telling me that the more I put in the more I can recover,” she told me.

Instead, they both decided to call it quits. Barry had lost £12,000, and Jane had lost £27,000.

“I’m horrified, numb,” Barry admitted. Both made dozens of phone calls in an attempt to recover their losses, but with no success. David Hunt has ceased returning Jane’s calls. She was aware that she had lost everything.

“I realized it was my birthday,” she explained. “It was the pandemic, and my family had organised a little outdoor get-together and brought me a cake, I was trying to be happy but I just felt so humiliated. I felt like I didn’t want to be on the planet anymore.”

It would take her months to get the confidence to tell anyone what she’d done.

Putting the puzzle pieces together

The Milton group’s operations had already been investigated by the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter and others, but the BBC went out to identify the key figures behind the global swindle.

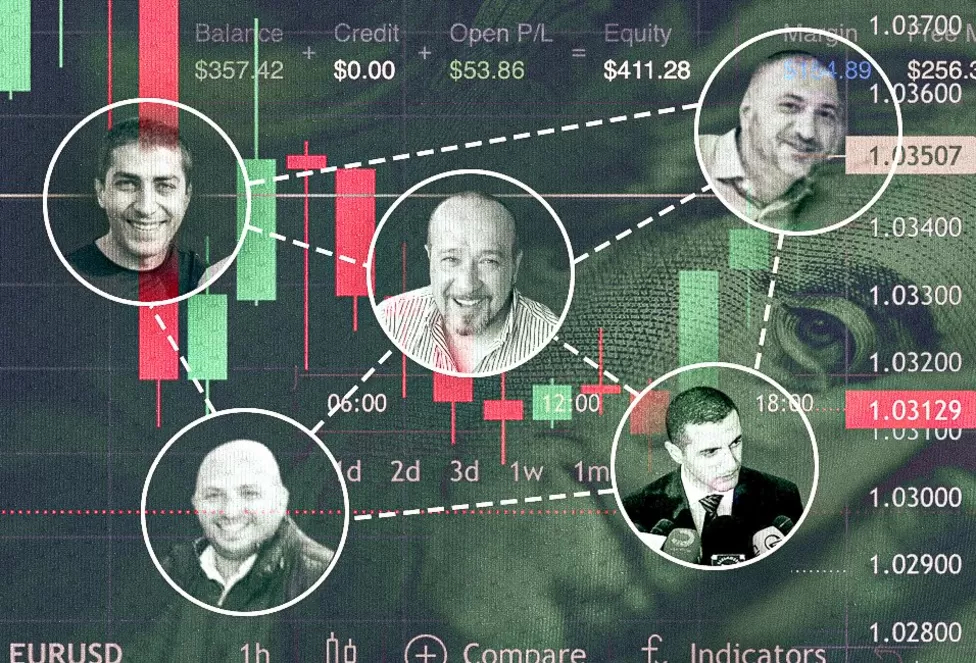

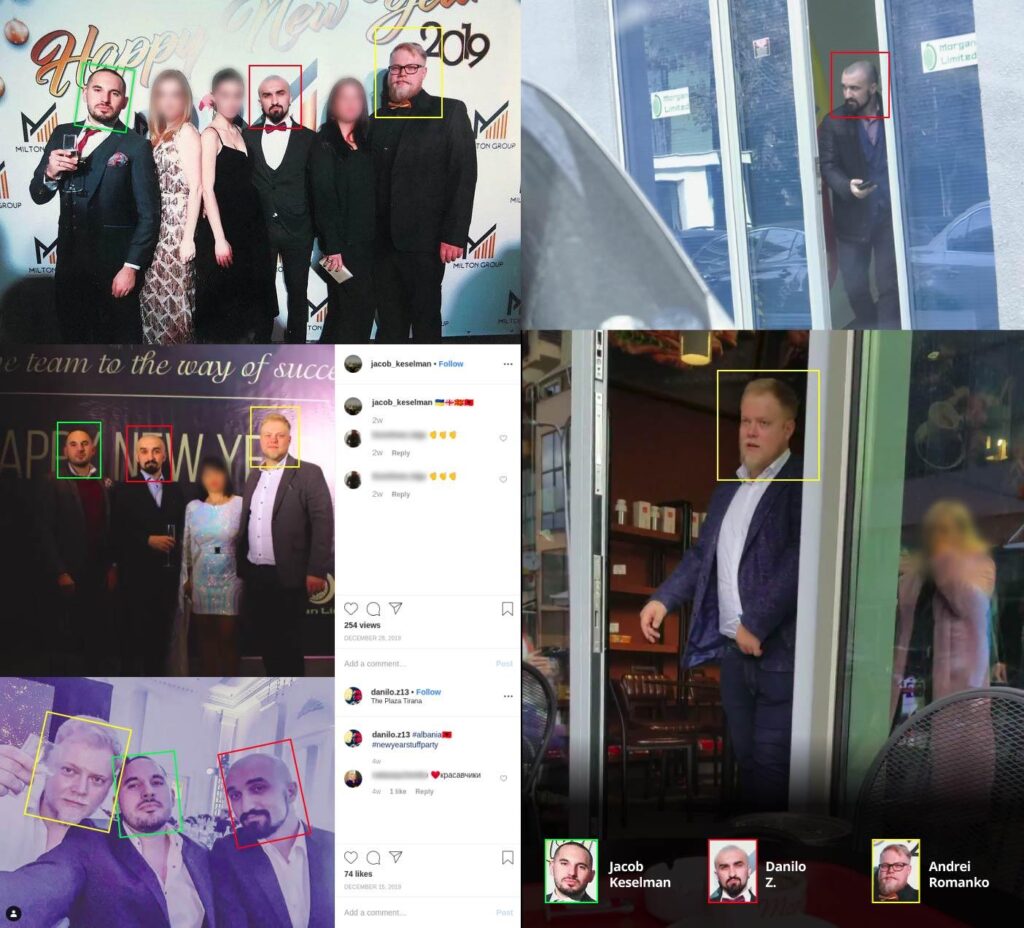

We started by searching through publicly available business documents to map the linkages between Milton group companies. David Todua, Rati Tchelidze, Guram Gogeshvili, Joseph Mgeladze, and Michael Benimini were all named as directors of Milton trading platforms or supporting software businesses.

We looked up the five names in the Panama Papers, a massive 2016 leak of information about offshore companies, and discovered that four of them – Tchelidze, Gogeshvili, Mgeladze, and Benimini – were listed as directors or senior figures in a group of linked offshore companies or subsidiary companies that pre-dated the Milton group.

Many of these non-Milton businesses could be traced back to one person: David Kezerashvili, a former Georgian government official who served as the country’s defense minister for two years.

Kezerashvili was fired as defense minister and later convicted in absentia of stealing more than €5 million from the government. He was living in London at the time of his conviction, and the UK turned down a request from Georgia for his extradition.

There were no publicly available records linking Kezerashvili to this pre-Milton network, but his name appeared repeatedly in the Panama Papers, identifying him as either the originator of the network’s parent businesses or one of their original stockholders. Kezerashvili appeared to be at the heart of that network behind the scenes.

Similarly, there was no publicly available documentation linking Kezerashvili to the fraud companies and no proof that he had any direct financial stake in the Milton brands.

However, some former workers of Milton-related enterprises told us privately that they had direct dealings with Kezerashvili and knew him to be involved with the Milton organization.

On his personal social media profiles, Kezerashvili has regularly promoted fraudulent trading platforms. On the business networking site LinkedIn, he has almost entirely utilized his account to promote jobs and distribute posts about Milton-related businesses.

The BBC discovered several additional pieces of evidence connecting the former military minister to Milton Brands. Kezerashvili’s enterprises used a private email system with only Milton group companies as other users. His venture capital firm, Infinity VC, held the branding and web domains for companies that provided the scammers with trading platform technology.

EverFX

Kezerashvili also owns a Kyiv office building where the scam contact center marketing EverFX and the tech company that delivered the software were both searched by police in November. He also owns a Tbilisi office building that houses several of the same IT enterprises.

When the BBC reviewed the four top Milton Group men’s social media profiles, it became evident from images posted of wedding parties and other social events that they all had close social ties to Kezerashvili. Kezerashvili is friends with at least 45 people connected to the Milton Group frauds on Facebook, and one of the four top figures identified by the BBC is his cousin.

The BBC followed Kezerashvili to his £18 million London property and tried to speak with him, but he was unavailable. He told the BBC through his lawyers that he had no participation with the Milton gang and had not benefited financially from frauds. He stated that EverFX was a genuine business to the best of his knowledge, and his lawyers contended that other connections we discovered to the people and IT behind it “proved nothing.”

Scam victims download a trading platform, but some never make any real trades. (BBC/Joel Gunter)

Mr. Chelidze and Mr. Gogeshvili both vehemently refuted our allegations, claiming that EverFX was a legitimate, regulated marketplace. They denied any knowledge of Milton or any relationship between EverFX and the brands we discovered, claiming that they had misappropriated EverFX’s source code and brand in order to confuse users. They claimed that EverFX never had a crypto wallet and had no control over the distribution of funds by outside payment processors.

Mr Mgeladze further refuted our allegations, claiming that he has never controlled any call centers that misled investors and has no knowledge of the Milton group.

Mr Benimini did not respond to any of our inquiries. EverFX refuted our charges, claiming that they were a genuine and regulated business with properly disclosed risks. They claimed to have researched Barry Burnett’s case and determined that he was to blame for his losses.

In Jane’s situation, they informed us that her losses were the result of her transfer to an unrelated company. They stated that they had completely cooperated with the FCA and that no UK regulatory complaints were outstanding.

According to the FCA, EverFX and other similar trading names will be outlawed in 2021.

Sevilla FC told the BBC that they had no further interaction with EverFX after their contract with the company expired.

Last year, fraud accounted for more than £4 billion in crime in the UK, and internet investment scams are estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of pounds per year. However, victims have criticized British police for what they regard as a lack of action against scammers on behalf of British nationals.

Jane tried several approaches, both at home and overseas, to recover her missing retirement assets, but she was unsuccessful. The City of London Police in the United Kingdom took her report, but “nothing came of it,” she stated. Her bank, too, was unable to assist, “aside from writing a few letters.”

“And why should they, really?” she mused, shrugging.

So she did the only thing that came to mind. She went to a dozen internet review websites and reviewed the trading companies that had duped her.

“I just wanted to warn anyone else who might fall for it,” she told me.

“I put a lot of effort into that. I hope someone sees it.”